Though most of us do not wear them, many can identify a sombrero, a fez, an Aussie bush hat, a Tam O’Shanter, a Glengarry, the Alpine Tyrolean hat, the Russian fur ushanka, a Greek fisherman’s hat, the conical straw Asian hat, the kippah, the kufi, bowler, top hat and beret.

Headwear is not only visually entrenched in our society; hats contribute to our verbal communication in descriptive and comparative ways. Most, if not all, of us will understand the many idioms and expressions derived from hats. Recently, I was invited to curate and lecture on a hat exhibit at a local museum, and I eagerly threw my hat in the ring. I wasn’t sure how to approach the subject, so I had to put on my thinking cap and make sure I didn’t speak through my hat, or I might have my hat handed to me. Surprisingly, the hat exhibit became one of the museum’s popular displays.

We often hear people described as mad as a hatter, wearing more than one hat, keeping something under their hat, pulling something out of a hat, pulling a hat over someone’s eyes, or someone who’s willing to eat their hat. And most of us are familiar with the expression, “If the shoe fits, wear it,” which is not the original expression. Originally, the expression, which originated in England and dates from the early 1700s, was, “If the cap fits, wear it.” The “cap” being referred to is the fool’s cap, a brightly colored cap with drooping peaks from which bells hung (you’ll see it on a joker in a deck of cards). In the United States, inexplicably, the cap became a shoe – perhaps a remnant of our revolutionary spirit.

Audrey Hepburn, on the set of 1961’s “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” knew how to wear a hat!

Paramount Pictures/Corbis via Getty Images

Someone may have told us to hang on to our hat, that home is where we hang our hat, that something is old hat, hats off to you, to pass the hat, or that something is a feather in our cap. How many of us have ever told someone, “Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?” Not you? Well, perhaps you don’t have in-laws (only kidding, maybe).

We may have done something at the drop of a hat, pulled something out of a hat, approached someone with our hat in hand, looked for something to hang our hat on, hoped our hockey team performed a hat trick, or lastly, been described as someone who wears a ten-dollar hat on a five-cent head. In Texas, there is a descriptive hat expression for someone who is all talk and has no substance: “All hat and no cattle.”

You may laugh at these hat clichés, but the point is that even though we no longer routinely wear them (except for the ubiquitous baseball or knit caps), hats are so ingrained in our culture that we continue to use and be familiar with these idioms and their meanings.

Hats have been around for thousands of years. Hats have been depicted on figures in murals discovered in Greece and Egypt that date back more than 5,000 years. In most countries, it was once highly unusual to encounter a person not wearing a hat. Throughout the world, hats were as much a part of everyday wear as any other article of clothing. In fact, in 1571, Queen Elizabeth I decreed that everyone should wear a hat on Sundays and holidays or pay a fine.

There was a time when it was highly unusual to encounter a person not wearing a hat. In fact, in 1571, Queen Elizabeth I decreed that everyone should wear a hat on Sundays and holidays or pay a fine.

Getty Images

Even the Christian Church recognized the significance of hats, and for this reason, in addition to some questionable Biblical references, the social connotations of hats are one reason why men remove their hats in church. Because hats typically denoted social status, the removal of hats in the church was meant to signify that all men were equal in the sight of God. Of course, even with no hat in church, a man’s wealth was known by the pew in which he and his family sat – which kind of defeated the sense of equality.

During the late 19th to the early 20th century, the wealthy upper classes distinguished themselves from the general public and even each other by dressing extravagantly and expensively. It was a time of conspicuous consumption where members of the wealthy class were identified by the cost of their possessions. A person couldn’t drag around their house, furnishings, carpets, and silver, but their clothing went with them everywhere. The amount of lace and beading on a dress or the number of gems on a neck, wrist, or finger let the world know that you had money and indicated you were from the upper social classes and, as such, better in every way than the average person. It was the same with hats. Large hats with a profusion of feathers and an extravagant and costly hat pin were all indications of wealth. The type of person my gran would say was “Dressed like Mrs. Astor’s pet horse.”

There have been times when hairstyles influenced hat styles (the calash) and times when hat styles influenced hairstyles (the cloche). During the late 18th century, most women wore simple shawls as head coverings or hats made of straw, plain cotton, or wool. Upper-class women wore elaborate bonnets of silk and satin, often over a base of straw or a framework of cane or whalebone. During the late 18th century, women’s exaggeratedly high hairstyles required large hoop-structured bonnets known as a clash.

The calash, which is essentially a retractable bonnet, was typically made of silk stretched over cane or whalebone hoops. This calash dates to about 1780.

Calash bonnets were designed specifically to accommodate the large, elaborate hairstyles that were fashionable during the late 18th to early 19th century. No matter how high a woman wore her hair (twelve inches high or higher was not unusual), decency demanded she wear a head covering. The calash also protected hairstyles from wind and rain; some were even waterproof. The name calash is derived from the French word “calèche,” which was a type of retractable hood on a French horse-drawn carriage. When indoors, the calash could be worn folded back. Outdoors, it could be drawn forward with the use of a drawstring or ribbon. Wearing a calash indicated that a woman came from the upper classes.

BONNETS: THE DOMINANT HEADWEAR

Bonnets from left to right: Left: Brown Poke Bonnet of pleated, ruched, tucked, and shirred silk drawn over cane ribs, with a curtain cape flounced draped back, circa 1830s. This is also known as a draw bonnet where the body of the bonnet is drawn over and stitched to a cane, whalebone, or wire frame. Center: Anna White, born June 14, 1802, wore this leghorn straw, satin, and lace wedding bonnet for her wedding to Horace Peck on January 22, 1829, in Clarendon, Orleans County, N.Y. You’ll notice this bonnet has a very deep crown and a wide, exaggerated brim that prevents all peripheral vision. Right: Leghorn Shaker straw and palm Poke bonnet with a bavolet, circa 1820s. Leghorn straw is a fine-plaited straw. You’ll notice the small crown and elongated tunnel-like brim that extends past the face. Women kept their hair covered for modesty, tradition, religious beliefs, personal decoration, and protection from the elements. Bonnets were the predominant headgear for women for most of the 19th century. In a time before sunblock or sunglasses, a bonnet’s brim protected the face and eyes from the wind, rain, and sun, and the trailing bavolet protected the neck from sunburn.

During the 19th century, the bonnet was the dominant head covering for women, and there were many types: off-the-face bonnets, poke bonnets, and draw bonnets being the most popular. A bonnet covers the crown of the head and features a small or large brim that entirely frames the face, severely restricting peripheral vision. It ties under the chin. Many 19th-century bonnets featured a ruffle of fabric at the back meant to cover the neck. This ruffle is called a bavolet, which is the French word for flap. Bonnets were often lined and decorated under the brim with flowers, tucks, shirring, and ribbons.

Until the 20th century, most women wore head coverings in the home, known as day or house caps. House caps could cover the hair completely (mob caps), expose the hair just above the forehead, or simply sit on the crown (pinners). These house caps could be plain or elaborate and made of linen, cotton, or muslin embellished with ribbons, ruffles, eyelets, or lace. During the 1860s, Mary Van Saun chose a house cap with extensions called lappets. After 1890, day caps were worn only by elderly women.

Mary Van Saun in a house cap with extensions called lappets.

During the 19th century, a woman in mourning could be identified by her apparel; everything she wore was black. Bonnets of almost any black material were worn with crepe veiling. The crepe veiling had to be worn over the face whenever the mourning woman was out in public. The veiling was heavy, difficult to see through, and toxic. The black dye contained heavy metals, most notably arsenic. These dyes cause irritation, scarring, and respiratory illnesses. They were absorbed through the skin, mucous membranes, and respiratory tract. These toxins caused illness and, in some cases, even death. The term “widow’s weeds” is derived from the old English word for apparel, which in turn was derived from the Indo-European word “wedh,” which meant “to weave.”

Women in mourning were identified by their black apparel, including a bonnet with crepe veiling.

During the 1890s, women’s hats became narrow and tall, so tall in fact that they earned the nickname “three-story hats.” By the first decade of the 20th century, women’s hats remained tall but also became wider, often wider than their shoulders. These milliner’s monuments were held in place by hat pins eight to ten inches long and often as long as 12 inches. Tall or wide, these hats came with problems of their own when passing through crowds and doorways.

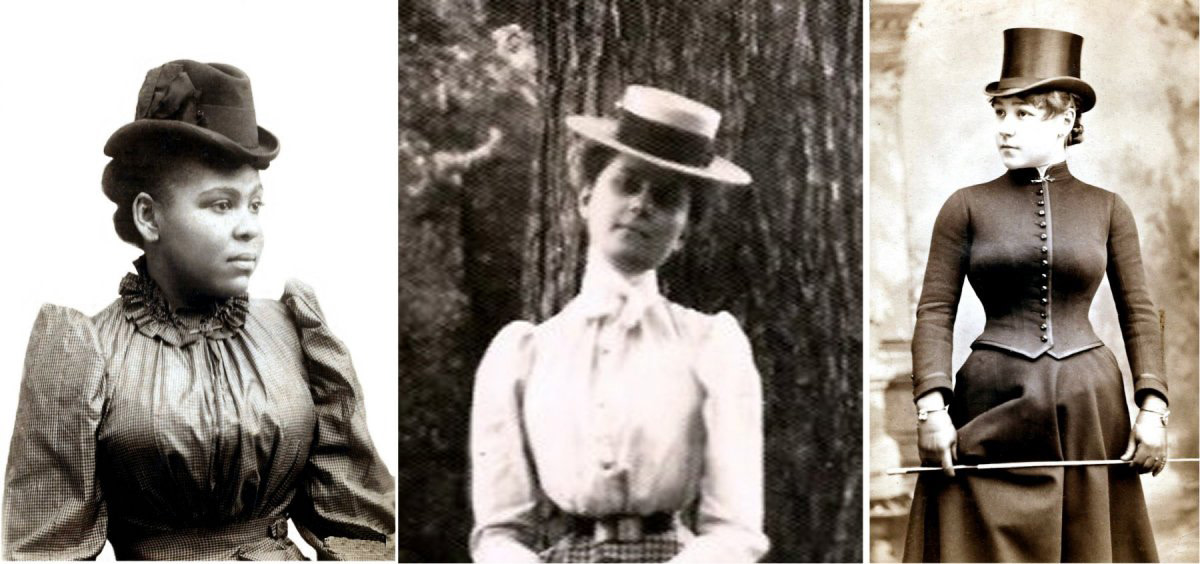

It might surprise you to learn that the fedora was originally a woman’s hat, as was the skimmer (boater) made famous by French singer and actor Maurice Chevalier. The woman at the left wore a fedora during the early 1890s, while her contemporary in the center chose a skimmer. Women also wore top hats when riding horses, as did this young woman during the 1880s.

PLUME BLOOM

In addition to their unnecessary height and gratuitous width, hats were further adorned with jewelry, flowers, and plumes from exotic birds or even the entire bird. With every movement of her head, a woman risked brushing, scratching, or poking anyone in her presence. Plumage on hats became so enormous and popular that herons and egrets, along with dozens of other birds, teetered on the brink of extinction. In fact, the Carolina parakeet, the only parrot native to North America, was hunted to extinction for its plumage.

1890s hats adorned with feathers. Big was the way to go during the mid-1890s when hats were side and tall, sleeves were like balloons, and the hem of a skirt could be three-and-a-half yards in circumference. Hats in the 1890s were so narrow and tall that they earned the nickname “three-story.” Bird feathers also became popular headwear adornment, much to the detriment of many birds.

The term “Plume Boom” refers to the first two decades of the 20th century when a number of migratory and native species of birds were hunted almost to extinction. Plumage was big business. From 1905 to 1920, more than 80,000 skins from the bird of paradise were sold in markets in New York, London and Paris. In 1911, prices for a single set of plumes ranged from $30 to $48, today’s equivalent of $1,100 to $1,400. In 1913, Eaton’s Catalogue, a Canadian mail-order catalog, offered a Bird of Paradise Aigrette for $12, which was a small fortune for the time, about $420 today. The aigrette was typically made of one or more white egret feathers.

Not unlike today, plays, movies, and celebrities have also influenced hat fashions. In 1907, a musical called The Merry Widow featured the lead wearing a large, ostrich-plumed hat. Soon, every fashionable woman had to have a similar hat, which became known as “The Merry Widow Hat.”

As a direct result of fashion, the population decline in large, beautiful birds such as the great egret, snowy egret, blue heron, green heron, flamingos, spoonbills, grebes, ostriches, and bird of paradise was so severe that Congress had to enact laws to preserve what remained of these decimated populations.

CONGRESS AND SHORTER HAIRSTYLES RESCUE BIRD POPULATIONS

Two women, Harriet Hemenway and her cousin, Mina Hall, were horrified by the decimation of these bird populations and lectured and encouraged women’s groups to boycott products decorated with feathers. They, along with William Brewster, created the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1897 and launched a boycott that led to the prohibition of wild bird feather trading in their state.

In 1913, the Weeks-McLean Law enacted by Congress outlawed hunting and interstate transportation of birds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 prohibited the importation of feathers and the slaughter of migratory birds for feathers. These laws were only part of the reason many bird species were brought back from the brink of extinction.

As strange as it may seem, the decline in the public’s desire for feathers was based more on a hairstyle than the desire to save these birds. Women’s shorter hairstyles, which became popular beginning in 1913, no longer provided a suitable foundation for the large, heavily plumed hats worn by their mothers and grandmothers. The shorter hairstyles and incredible popularity of the cloche cap made plume-hunting no longer profitable.

By the 1920s, the hatpin argument was pretty much over as hats became smaller and tightly fitted. The cloche, French for “bell”, was the most popular hat of the decade. Many young women eschewed hats altogether in favor of the bandeau or headache band, which will forevermore be associated with the flappers of the Roaring Twenties.

CHANGING WITH THE TIMES

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, hats were de rigueur for women. They ranged in size from the small Glengarry and simple fascinators to hats of outrageous proportions with veiling, snoods, beads, and bejeweled clips. Most people wore hats every day until the 1950s and 1960s, after which the popularity of hats rapidly declined. There are a couple of major reasons for this decline. Prior to people owning cars and utilizing mass transit, most people walked to their destination and hats were required as protection against the sun or inclement weather. As more and more people began to travel by car and use public transportation, the hat was no longer required and, in fact, became inconvenient.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, hairstyles for men and women became more important than the latest fashion in hats. For women, hairstyles like the poodle cut, bouffant, beehive, and pixie cut were styles meant to be appreciated rather than hidden beneath a hat.

For men, it was the Quiff, flattops, pompadour, duck tail, jelly roll, mop tops, and afros. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, many women only wore hats on Sundays, and then three major trends occurred: the requirement for women to wear hats took on a negative connotation of subservience, church attendance began to decrease, and by 1983, the Catholic church no longer required women to wear hats or head coverings in church.

It is interesting to note that during President Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, there was hardly a bare head in the crowd, and by Johnson’s second inauguration in 1965, there was barely a hat in the crowd.

President Kennedy in a top hat and wife Jacqueline Kennedy in her signature pillbox hat on Inauguration Day, Jan. 20, 1961. It was the beginning of JFK’s presidency and the beginning of the end of the reign of hats.

Getty Images

Although it seems like the hat’s demise happened suddenly, it actually began during the late 1920s with young people challenging the tradition. Perhaps one day, future generations will once again wear hats to distinguish themselves from their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Wouldn’t that be cool?

Few Hollywood stars look as lovely in a hat as Audrey Hepburn. The only question here: Is Hepburn wearing this enormous pink hat in a scene from 1964’s “My Fair Lady,” or is it wearing her?

Getty Images

You may also like:

Find Yourself a Hat for all Seasons, all Reasons

Antique Hatpins: Stylish Self-Protection

How Jacqueline Kennedy Became the Fabulous First Lady of Fashion